Classic Rock

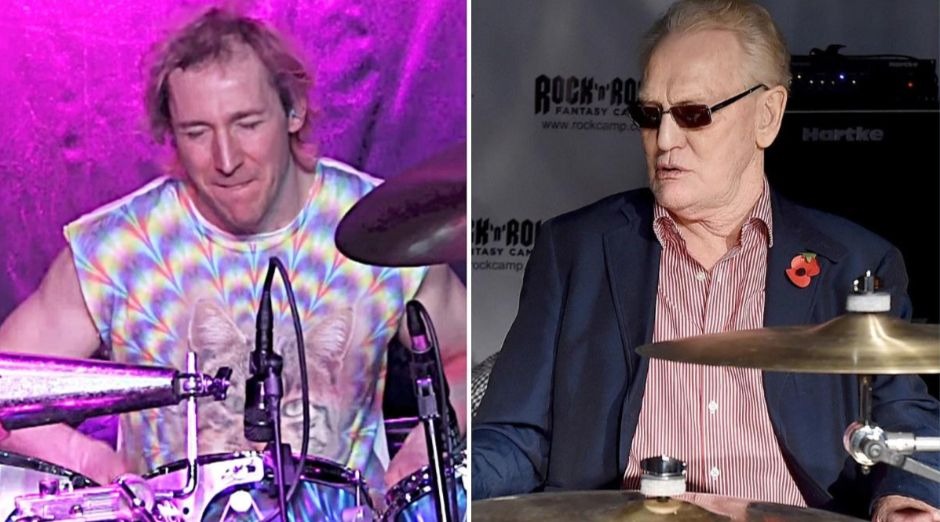

Ginger Baker’s son talks about the last time he saw his father

Ginger Baker was not an easy person to deal with, and his relationship with his son Kofi Baker wasn’t good, but in an interview with Rolling Stone, he revealed that the feud between them was resolved before the legendary drummer death.

The legendary drummer Ginger Baker drummer died on October 6, at 80, according to his family. The musician was part of the supergroup Cream with Eric Clapton (guitar and vocals) and the late Jack Bruce (bass and vocals), he was also considered one of the best drummers of all time. The cause of his death was not revealed, but Baker was hospitalized and the family even said a few days ago before his death that he was already feeling better.

Kofi, who is also a drummer, said:

“It’s kind of like he’s already dead. He’s disowned me so many times in my life. It’s like he’s been dead to me for a long time anyway.” Kofi rarely saw his father, and the times he spent with his notoriously ornery dad were not always easy.”

“I don’t know what went on the last 10, 15 years after the [Cream] reunion,” Kofi told RS a few days after his father died on October 6th at age 80 of complications from chronic-obstructive pulmonary disease. “I only saw him twice, 2005 and 2014, in the last, what, 17, 18 years or whatever it was. I emailed with him briefly. It was hard to talk to him on the phone because he was deaf, so it was kind of pointless.”

How are you handling your father’s passing?

I’m still processing it. I used to say to my girlfriend, “When he dies, I’m going to feel nothing.” I really didn’t think I’d feel anything. The asshole had to open up to me right before he died. I think if he’d stayed an asshole to me, maybe, it would be easier. But I didn’t think it would affect me the way it affected me.

You talked about your conflicted feelings about your father with us last year.

The last interview I did with you guys, I was like, “No relationship with him. He fucks me off every time.” I feel bad for saying that shit because I may have hurt my dad, saying some of the stuff I said.

Two months ago, I just thought, “Fuck it. I’m going to England. I’m just going to sit down with my dad, and I’m just going to tell him exactly how I feel because he’s getting old.” I emailed him and, surprisingly enough, the email back was really nice: “Nice to hear from you.” I was really looking forward to that meeting. And then, two and a half weeks ago [in mid-September], he went into the hospital. He just had this shutdown [of] everything, and everybody thought he was going to die. That was a week or maybe five days before I was meant to come out. They said, “You’d better get here.”

Then everybody said, “Oh, he’s actually getting a bit better.” And I said, “OK, he’s going to pull through. My dad’s not going to fucking die.” I thought he was going to outlive me. When he fell off the roof in Colorado [in the Nineties] and went to hospital, he was trying to get out of the bed. They were saying, “No, don’t move.” And he’s like, “Get off me! Let me out!”

And amazingly, he stayed in [the hospital in Kent, England], and he got a little bit better. Six days later I went to see him.

Can you take us through that visit?

I flew in Monday morning [September 30th] and went straight to the hospital and walked in. He wasn’t out of his bed, but he was sitting up. He was blowing his nose, asking for tissues, drinking a bit of tea and dunking his biscuits in the tea. I sat quietly with him at first, then just thought, “What the fuck? I’ve got all this stuff I want to tell him.” And I just started telling him about how I’m doing his music and I’m keeping his legacy going.

I said to him, “Hey, I’m learning ‘Blue Condition,’ and I’m doing your stuff.” He taught me how to play, so the main thing was being able to tell him, “Dad, I’m carrying on. I’m keeping everything you taught me, all the secrets and everything. I’m going to keep it going as well as I can now.” And he was just smiled, and it was just amazing.

I’m used to my dad blowing me off or not talking about anything. But he was a different person. It was like his eyes lit up, and I told him stories about the past and everything, like the time he was smoking a cigarette while he’s pouring gasoline all over me, and I’m holding a funnel pouring into the truck. I told him that, and he laughed [laughs]. It was so amazing to actually connect with my dad. It still puts chills down my spine now. [Voice breaks.]

Was he able to speak at all?

He couldn’t really. And that was probably why I could talk to him. It was really hard seeing my dad like that, because he’s always been such a fiery guy. But it was just beautiful because I got to talk about music and not get shut down. It’s a good way for me to remember him.

It’s just hard thinking about the last moments I had with him … my dad’s face, his eyes, and the way he reacted to me — he’d never done that. I don’t know if people change right before they die. I think he knew he was going to die, and I think he relaxed at the fact that he could be himself. He just dropped that hard exterior.

Seeing him right before he died, I really think that was my real dad. Underneath all that temper and stuff I thought he was a really loving person. I just don’t think he could say it to me. I struggle with my girlfriend with that. She always says, “I love you,” and I never say, “I love you” back. It wasn’t how I was brought up. I wasn’t brought up to [say], “I love you, I love you.” It was more a kind of thing that you know your dad loves you, and you don’t have to have him say it kind of thing.

I did say it to him in the hospital, “Dad, I love you.” And he acknowledged it. And I’ve never been able to say that to him and I just felt that I had to.

What happened in the end?

After seeing him, it seemed like he got better. People were coming up to me and saying, “Don’t believe everything you hear. I think he’s going to pull through.” I was going to go see him on Monday, my day off [October 7th]. Of course, he had to die Sunday morning [the day before]. So he had his last laugh on me, I suppose. I did tell him before he died how I loved him and everything, so I think I got it out. My dad’s such an asshole for fucking dying when it finally all comes together, but I think this is how it had to happen.

What contributed to his death?

The problem was he wasn’t getting the nutrition. He was just drinking tea and eating biscuits. The nurse and the doctor were saying that when you’re weak like that, you need real nutrition. But I don’t think he could hold it down, and he died in his sleep. It was peaceful. Kudzai [Baker’s wife] was with him and she said he just faded off to sleep. Stopped breathing. It was [like] the whole body was just saying, “Enough.” I’m happy that he went in a good way, but I’m sad I didn’t get one more day with him. I’m just so happy that I got to hold his hand [voice breaks].

You had a show with your band, the Music of Cream, that night.

It was really hard. If my dad is up there, wherever you go when you die, is he looking down on me? Is he seeing this extra stuff I’m adding? But the conversation I had with him, it seemed like he was just happy that I was doing it. But every time I thought about my dad that night, it was so hard to play. The drum solo was really hard. It was a really emotional thing.

What was your first sense that your father was a rock star?

I never really kind of realized, I suppose, how big he was. When I was six, my mom took me took a concert. And my dad said, “Make sure I know you’re there.” But I was six years old in the back of a concert. So that was kind of, I suppose, the realization. But I don’t think it ever really dawned on me because I grew up with that stuff. I thought everybody’s house was multi-colored walls, and everybody’s house had gold records on the walls. I thought that was the norm.

What was it like having him teach you to play drums?

He taught me [drums] up until I was seven or eight, and then he left home. And then it was hard for me to get lessons. I had brief lessons with him. I went to see him secretly; my mom wouldn’t know. I saw my dad again when I was 14; we went out to Italy [where Baker was living]. And then I started to see him briefly at 15, 16, getting more lessons. I went to stay with him in Italy.

I had brief relationships with him, but they were hard. It wasn’t like, sit down and have a cup of tea with my dad and have a laugh. It was more like, “You’ve got to get more technique. You’ve got a great feel; you don’t have enough technique.” And I went home, practiced for like eight hours a day for like five or six years. Then went to see him again and he’s like, “Now you got too much technique! You got to forget about the technique and just play.” It was like I was always never good enough for him. I was always battling to be good enough. I don’t think he thought about it, but putting me down just made me want to prove myself to him harder.

In Colorado, I set the drums up and we were going to do a duet, but we had a big blowout. I said, “Dad, do you even care about me or anything?” He said, “No, I don’t fucking care.” And I was like, “That’s it.” And I stormed off, and I’ve kind of held that in my life, that my dad doesn’t give a fuck about me. And he did, he really did. I just don’t think he could express it.

What have you learned about his technique now that you’re playing with Music of Cream?

When I first started playing it, it was more just how innovative his drumming really was, especially the polyrhythm stuff. Once I started going to double bass drums and when I started playing the Cream stuff, I realized that how he was playing was really just that left foot over from the hi-hat onto the bass drum. And I did that, and I was like, “That beat seems familiar. That’s the beat.” It’s the double-bass-drum part with the left foot playing the upbeat on the bass drum, like a jazz thing. It’s just taking those jazz things and moving them around the kit and bringing them into rock drumming.

Rock people didn’t like him because he was too jazzy. Jazz people didn’t like him because he was too rock. He never thought he was a rock drummer. If you said, “Dad, people say you’re a rock … ,” [he’d say] “Fuck off! I’m a jazz player.” He was a jazz drummer playing it rock. And that’s what made him so special. It was a new thing back then, people mixing styles of music together. That will probably be his legacy, the first guy to put jazz drumming into rock.

My dad’s left me his drums. I’m going to take the snare drum he played from the beginning. I had it when I was kid when I was 10. And he went, “Oh, you got that drum. That’s mine.” And he took it back and gave me some crappy drums. But now I’m going to give it to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

How does his style compare to modern drumming?

Nowadays, the drumming is so simplistic; it’s a backbeat. For my dad, the drumming was an integral part of the music: the 5/4 bolero on “White Room,” the backwards beat in “Sunshine of Your Love.” He didn’t play drums like a backbeat. He’d actually record riffs, and he would play stuff that complemented the music. My dad had this amazing ability to put in one or two fills in a song that just made the song. And that’s what, to me, a musician does. Nowadays, it’s like, “What do you call a drummer? Someone who hangs around the musicians.”

The reason they’re dancing so much on the stage now is because the music’s so boring. When you went to see Cream back in those days, you closed your eyes and felt the music. Back in my dad’s day, that’s what he was doing — he was a musician. When I was teaching drums, I was teaching kids who didn’t know who my dad was. He’s touched people who don’t even know he’s influenced them. I just love playing his stuff now, and this is what I’m going to do now. I’m going to keep doing my original music, but my focus now is keeping my dad’s shit alive.